cl-notebook Update

Fri Aug 8, 2014So I finally got a semi-contiguous stretch of time together in order to work on this and this. A few tiny cosmetic changes, which I'm still not done with, a few deep behind-the-scenes changes that you shouldn't have to care about, and one major front-end feature.

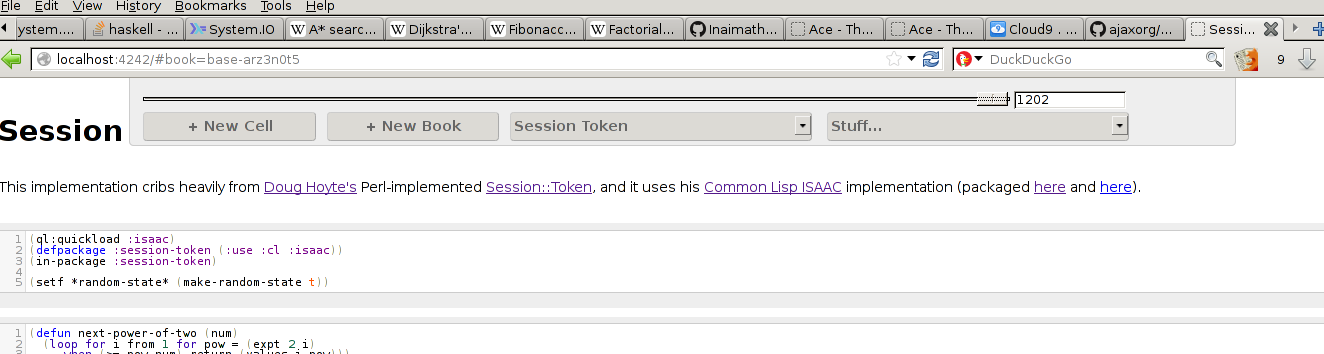

That's a history slider. Which I've been talking about all over the place, but always in the context of "man I gotta get on that". So I finally got, and this is what it currently looks like. It's surprisingly snappy, given what's going on behind the scenes. rewind is an ajax hit to the server for re-calculation of the next notebook state, the result of which is re-rendering the entire screenful of cells. It's debounced at 10 units, ostensibly msecs, but it really doesn't feel like it.

By the way, this is the main thing I wanted to experiment with using cl-notebook. I mean, yes, literate programming, and yes easy-to-use CL editor, and yes multi-user editing, but that's all commentary. The real thing I've been trying to get at from the beginning is total history tracking. If you've talked to me about it in real life, my pitch has consistently been something like "I don't want to lose any data ever again". It's why I use a particular, hand-rolled storage system, and why I have fervently insisted on append-only operations.

Qualitative Differences

I remember a talk that Linus Torvalds gave at Google, in which he compared git to centralized systems like [svn](https://subversion.apache.org/) and [cvs](http://savannah.nongnu.org/projects/cvs). The claim was that cheap branches didn't just let you make more branches, but that they completely changed your behavior during the development process. You could suddenly throw up per-feature and experimental branches, do some prospective development, then merge if it amounted to anything or drop if it didn't. I'm sure those of you who still remember using svn agree this was a big step forward. One of the companies I worked at early on used svn for source control and merging/branching can only be described as an ordeal. It was a feat reserved for the veteran programmers on the team, it basically took two days or so at the end of every cycle, and it usually sapped some time from any developers that were involved in contiguous or overlapping functionality. Because any file that was touched by more than one human would have to be manually reconciled by a human. Every once in a while, the network connection to our central repo would crap out during one of these operations, and then the real fun would begin.

None of that happens anymore. In fact, people who grew up with git probably think what I described there is fucking insane, and they're not wrong in retrospect. Today, we're not just doing the same thing, but faster. We've got completely different workflows that take advantage of decentralized source control with easy merging. There really is a qualitative difference between having expensive branches and almost ridiculously cheap ones.

I think there's a second one between "ridiculously cheap branches" and, effectively, "free branches".

Not sure, obviously, that's why I'm running the experiments, but it seems that if you really wanted to, you could turn the current workflow on its head.

Workflow

Here's how you work with git, or any distributed, externally mediated history system:

- do some development

- get to a release, tag it

- start up feature branches for the new stuff

- if you have experiments to run, or something risky to do, start up separate branches

- if a bug is reported in the meantime, fix it in your

masterbranch andcherry-pickthe changes out to the others - merge development and successful experimental branches, start next release cycle

Not bad. And it certainly beats any centralized, externally mediated history system. But there's another way. If your work was being tracked on a minimal, per-change basis, what you could do is

- do some development

- get to a release, tag it

- do all of your feature/experimental work in the same place, rewind out when you get in trouble

- go to 2

I'm not going to talk about merging separate timelines, because I haven't thought about it thoroughly enough, but it doesn't seem impossible. The important part of the above comparison is that tracking full history frees you from having to know when a thing you're about to do will turn out to be much harder than expected. It'll be tracked regardless, so you can gracefully back out of any big changes you make in the meantime.

Interaction

You can see the basic interaction in that video above. To summarize:

- there's a slider/input combo at the top of the control bar of every notebook

- if you change them|1| appropriately, you'll see some point in the history of the notebook

- if you try to edit anything at that point, the system will automatically fork a separate notebook and apply the changes to that. This way, you can edit starting from some point in the past, without losing the earlier timeline.

That last item is still the subject of some internal debate, by the way. Do I want auto-forking, or do I want to make changes to the past of this particular notebook? I obviously don't want to do the second one naively, because that would imply re-writing the entire history of a particular notebook in a destructive manner, which goes against this "never lose data again" goal I'm working towards. But something more complicated like a fork/apply-edits/re-merge sequence would let me get both full data retention and the ability to mess with time.

It sounds expensive, but this project has repeatedly taught me that very expensive sounding things might still be cheap enough to do a few hundred times per second. The question really, is how do I manage those forks. I still don't have a good idea for how to do that properly, so I think I'll stick to the current implementation for the time being, but I'm still thinking.

Other Changes

Some other stuff had to be changed here. Two main things, really.

First, a notebook is no longer keyed off of its title, which is mutable and not unique|2|, but its filename, which only changes when the user does it manually and is unique among living notebooks. This means that the less intuitive notebook filename now needs to be used as the page hash of an editing session. Mildly annoying, but I can't see a good way around it, given what I want to be able to do.

Second, I've sat down and put fact-base:change! to good use all over the place. Previously, the same thing was achieved by doing a delete! followed by insert! on a very similar fact to the one that was just deleted. It had roughly the same effect, but wasn't atomic. Which is why, if you try to go through the history of a notebook made before the change, you'll see cells go empty before they get new content. These were actually separate history states at that point. All the change! change is meant to do is get rid of those intermediate empty states.

Oh, I also added a tag! function to fact-base, but haven't used it or thought about it very hard yet. I probably will before too long, but one thing at a time.

Next Steps

I think what I've got is close enough to real-time for human purposes. Doing much better would involve a lot of low-level, fiddly work and the sorts of synchronization problems I really don't feel the need to tackle. Especially since the final payoff would be pretty minimal. I'm still missing a bunch of what I consider basic editor features, such as s-expression navigation, automatic indentation, good autocompletion and argument hinting. And given that this is meant to be a Common Lisp development system, it's also missing integration with a few key libraries, namely [quicklisp](http://www.quicklisp.org/beta/) and [buildapp](http://www.xach.com/lisp/buildapp/).

So I think it's about time I tackled all of that.

Footnotes

1 - |back| - Slide the slider, change the value of the text box.

2 - |back| - Specifically, if you fork a book, then look into the forks' history, at some point it will intentionally have the same title as its parent.